- PagerDuty /

- Blog /

- Digital Operations /

- Has the firefighting stopped? The effect of COVID-19 on on-call engineers

Blog

Has the firefighting stopped? The effect of COVID-19 on on-call engineers

With digital becoming the primary channel for work, education, shopping, and entertainment in the last 18 months, it’s no surprise that workloads for technical teams and on-call engineers have increased.

Data from PagerDuty’s inaugural platform insights report, The State of Digital Operations, highlights this reality. As of July 2021, the average number of events managed daily by PagerDuty is 37 million, with 61,000 of those being critical incidents. Critical incidents are defined as those from high urgency services, not auto-resolved within five minutes, but acknowledged within four hours and resolved within 24 hours. According to our data, the number of critical incidents grew by 19% from 2019-2020.

For many teams responsible for supporting this always-on world, “firefighting” has become the typical mode of operation. But this digital shift is here to stay, and the workload is not going to reduce. Over the next few blogs, we’re going to dig further into the findings from our platform data and explore how the growing volume of real-time work is increasingly burdening technical teams. In this first blog, we’ll share how this firefighting affects burnout levels, how to classify and quantify interruptions, and what teams can do to avoid attrition.

Risk of burnout a real threat

Life as an on-call engineer is always hectic, but we looked specifically at what the experience was like in the last 18 months. Comparing the hours worked in the first 12 months of the pandemic (March 2020-March 2021) to the preceding 12 months (March 2019-March 2020), we can see that more than a third of PagerDuty users worked far less consistent schedules in 2020 than in 2019. On average, individuals are working the equivalent of two extra hours per day. This totals an extra 12 weeks of work over the course of a year.

Humans sit at the heart of incident response. Being aware of overwork is critical for businesses, managers, and technical teams alike. The continual pressure, disruption to responders’ routines, and the impact on individuals’ lives is a recipe for burnout. And it’s important to remember that not all interruptions are created equally. Some take a bigger toll on the wellbeing of on-call engineers.

Interruptions around the clock

An interruption is a non-email notification—including a push notification to a mobile phone, an SMS, or a phone call—generated by an incident. Looking into our platform data, it’s clear that how many interruptions a responder faces, and the time of the day they are interrupted affects their level of burnout.

The total volume of interruptions increased 4% in 2020 from 2019, with some teams hit harder than others. This is especially true of smaller companies where 46% of users are interrupted each month compared to 30% of enterprise users. Smaller organizations are often in hypergrowth mode and may lack the resources of larger businesses, but managers must balance the drive to grow against the risk of burned-out technical staff.

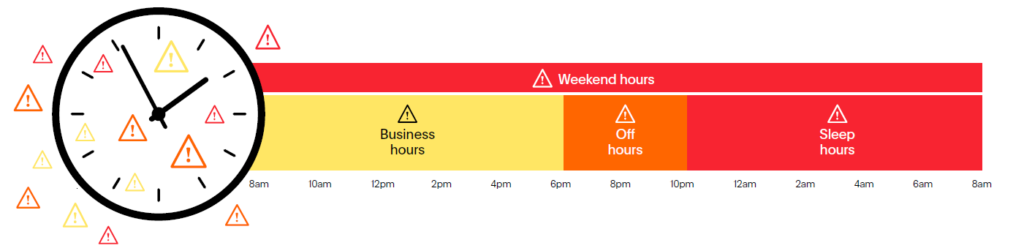

The time of day an interruption happens is also important. Between 2019 and 2020, there was a 9% increase in off-hour interruptions and a 7% lift in holiday and weekend hour interruptions. We define the types of interruptions as follows:

- Business Hours Interruptions: Sent between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. Monday to Friday in the user’s local time.

- Off Hours Interruptions: Sent between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. Monday to Friday or during 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. over the weekend in the user’s local time.

- Sleep Hours Interruptions: Sent between 10 p.m. and 8 a.m. in the user’s local time.

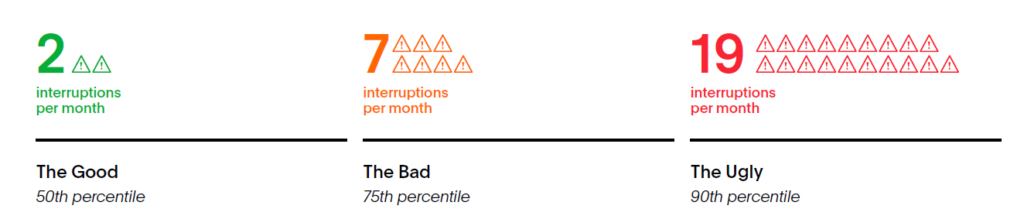

When engineers are on call, they understand that they might get interrupted. But there is a clear difference between an interruption sent at 3.p.m. and one at 3.a.m, and the subsequent impact on the person. We broke down the analysis of off-hours interruptions further and identified three distinct cohorts.

Responders in the “good” percentile experienced 2 non-working hour interruptions per month. Those in the “bad” 75th percentile, who we identify as “overworked,” have seven non-working hour interruptions a month. And for those in the 90th percentile, it certainly is “ugly.” These responders are on the receiving end of 19 non-working hour interruptions a month. That is three times as many as those “overworked,” and ten times as many as the median responder.

Tackling the Great Resignation

Operating under this kind of stress is clearly not sustainable. The result can be employee attrition. Our data shows that the more often people were disturbed in their off hours, the more likely they were to leave the PagerDuty platform (our proxy for attrition). The profiles of responders leaving the platform showed they experienced off-hour incidents every 12 days compared to every 15 days for remaining users.

Currently, many sectors are in the midst of what economists are calling The Great Resignation. Employers can’t afford to lose talented and skilled technical staff because they are burned out. Organizations need to actively manage incident response workloads and mature their on-call processes to promote better team health and avoid overworking their people. Here are three ways teams can take back control.

- Measure on-call qualitatively and quantitatively with operational analytics. Teams can measure on-call workloads by looking at the volume of interruptions and the time spent on-call. They can then combine this data with other metrics, such as time of day, severity, number of escalations, to identify those individuals most at risk of burnout and contextualize their on-call experience. PagerDuty Analytics collates data across incidents, services, and teams, and turns it into insights and recommendations to help managers understand the burden on on-call teams.

- Stop getting interrupted by inactionable alerts. When responders are being bombarded with alerts, it creates a stressful environment where everything is “urgent.” Intelligent alert reduction cuts down on this noise, allowing responders to focus on the incidents that really need attention. You can tune alerts to share the right amount of information your teams want, even if that does mean allowing certain amounts of specific noise to cut through. Event Intelligence is PagerDuty’s AI-powered tool for digital operations. Its adaptive learning algorithms separate signals from noise and only alerts teams on genuine incidents that require human intervention.

- Create automation sequences that can auto-remediate without human intervention. Another way of taking back control is to give responders access to self-service capabilities to resolve an issue, without needing to escalate to a subject matter expert or even to involve a human at all. Teams can document incident response processes (e.g scripts, tools, API calls, manual commands) into a runbook that can be automatically triggered to resolve an incident. Incidents are resolved in real-time, with minimal stress. Check out this eBook on Runbook Automation from PagerDuty and Rundeck to learn more.

As we adjust to the new normal, firefighting mode must be matured into a more proactive and preventative model of incident response to mitigate burnout and attrition. An always-on world needs a new approach that helps businesses to respond effectively when an incident does strike, and reduces negative impacts on the teams responsible for supporting digital services. Proactively managing workloads means that incidents are dealt with in real-time, every time, while reducing the burden on on-call engineers.

To learn more about our platform data learnings, check out the rest of our State of Digital Operations report or watch our Perspectives on Digital Operations: The Volume and Human Impact of On-Call and Real-Time Work webinar.